AI-Native Databases: The Missing Layer Behind Reliable CoPilots

Jan 30, 2026

|

Amir Ben Ami | Head of AI @ Linx

An AI-Native database isn't a vector store; it's a schema designed with semantic clarity and automated metadata enforcement that allows LLMs to query it without hallucination.

For the past two years, I've been building agents that expose data residing in different databases. Here, I'd like to share some actionable insights I've gathered along the way.

At Linx, we had to handle extremely high-scale databases for large enterprises. Building agents that perform well with low latency and high accuracy is hard, and the list of challenges is long.

Which model should you use? Should you fine-tune? How do you consume historical query data, and should you perform active learning? What about orchestration, do you go with an agentic framework or keep it vanilla? How do you respond quickly to investigations running against high-scale databases? And how do you rationalize cross-domain information spanning Business, Security, Governance, and Compliance?

These are just a few of the questions we had to answer.

While all of these topics are important, I'd like to focus on a different angle, one that turned out to be even more crucial.

When building an agent, engineers tend to equip it with tools that allow it to query the data, expose the schema, and assume that the agent will perform well from there. However, that's not the case.

Imagine you're exposing a schema to a junior analyst who's proficient in your database query language. Will they be able to answer questions about the data correctly? In reality, no. In the following sections, I'll explain why not, and how we solved it.

What Differentiates AI from Humans?

Jeremiah Lowin, in his excellent talk, presents criteria for how LLMs differ from humans when consuming data from APIs. Here's my version for the database problem, which is slightly different:

Capability | Human Analyst | AI Agent (LLM) |

Discovery Process | Heuristic & Intuitive: A human runs DISTINCT or LIMIT 5 once to understand an enum or date format. They cache that "vibe" in their brain. | Repetitive & Expensive: Without memory, an AI must re-run discovery for every new session. This adds latency and increases the risk of "discovery hallucinations." |

Iterative Logic | Stateful: If a human gets an error, they tweak the query and move on. They don't need to re-read the entire schema documentation to fix a typo. | Token-Heavy: Every iteration (error → fix) requires resending the entire conversation, schema, and all instructions. This creates "Context Bloat," where the AI eventually loses sight of the original goal. |

Context & Memory | Deep Accumulation: Humans build a mental model over months. They learn which tables are "legacy" and which fields are the "source of truth" through experience and Slack conversations. | No Memory: They only remember what we squeeze into the last ~200,000 tokens. Without explicit "AI-Native" markers, they treat 10-year-old legacy fields with the same importance as your core production data. |

Real-Life Examples of Non-AI-Friendly Cases

Bad Naming: We had a field called is_external, which actually means “is the email domain external to the organization.” It does not mean the user is external, it's a property of the email itself. That naming alone caused repeated mistakes when the AI was asked about external users. The AI assumed the user was a guest, leading to incorrect security audit reports.

Different Lingo: We use a graph database. The relationship between a user and their accounts was represented by an edge named owner_of. But the relationship between a user and their secrets was named responsible_for. When someone asks "Who owns this secret?", the agent tries to generate a query using owner_of, even though we explicitly mentioned what types of edges exist and how they operate. As a result, the query returned no results, even though the data existed.

Design for Performance: We have an accounts collection, where each account represents a human in a specific application. We chose to keep the application name and data in another collection, storing only the app ID in the account document so that one could join them to get the app name if required. This was done to support the use case of app renaming without migrating many documents. In reality, since 98% of queries from accounts required the app name, this caused a huge waste of tokens as the same join query was generated over and over again. (We also found it to be non-performant for the non-agent use case as well.)

Fields That Shouldn't Be Exposed: We had many internal and legacy fields for feature flags, processing states, migration leftovers, and version counters. Things like read_for_processing and migrated—humans learn to ignore them. In some cases, the agent treats them as meaningful and starts weaving them into answers; in others, we're just wasting tokens.

Why Database Schemas Are Built This Way

Your database dialect is set by how your company talks and names things, but customer language doesn't always match your schema's language. The moment users ask questions their way, the gap shows up immediately. While engineering teams optimize for performance, storage, and clean abstractions—all valid priorities—AI agents need something entirely different: clarity and self-explanatory semantics. This disconnect persisted because, until recently, these systems were not customer-facing, and engineers who had to query the data saw no reason to complain.

Why Building a View Is Not Enough

In the MCP presentation, the suggestion is to curate a new API to be consumed by an agent alongside the existing API. One might say, "Let's build a view on top of the existing database and enforce these concepts there." However, I don't think this approach works here, for several reasons:

Views drift. New fields get added to the real model, someone forgets to update the view, and suddenly the CoPilot can't answer questions about new features. For customers, if the product and the AI's "understanding" (the view) diverge by even 5%, the Agent becomes unreliable.

Views might require duplicating the data, which is costly (depending on the type of view).

The concepts here aren't only good for an agent, but for anyone trying to access the database. The same mistakes made by an agent are also made by engineers who build queries and assume they correctly understand the schema.

This doesn't mean we can't create new fields to be consumed solely by the AI, or that there won't be fields the AI should ignore. But the majority of data should be streamlined with a process designed to ensure it is AI-Native. There's nothing more frustrating than finding out a day after a new feature was released that it's not exposed by the CoPilot.

Why Can't We Use a DAL (Data Abstraction Layer)?

A Data Abstraction Layer (DAL) is a software layer that sits between the application and the database, providing a simplified interface that hides the complexity of data storage and retrieval.

A DAL addresses many of the issues raised above. It focuses on outcomes, inner joins are already set, fields that should be ignored are removed, and it's usually explainable and optimized for performance.

However, using a query language is almost like writing code. You can do much more, and DALs are always limited by how they were designed and built. With open-ended queries, the possibilities are as broad as the database creator allows—which is usually what customers expect when asking a CoPilot about their data.

DALs are rigid; AI needs the flexibility of SQL but the safety of a DAL.

How We Solved These Challenges at Linx

At Linx, we weren't just dealing with flat tables; we were managing a massive Identity Graph. This added a layer of complexity where "truth" isn't found in a single row, but in the relationships between disparate domains—merging Business, Security, Governance, and Compliance data into a single coherent view.

We decided to build multiple tools to help our CoPilot answer customer questions. On the database side, we expose everything by default—new fields require a description and should be immediately discoverable by the agent. Alongside this, we also expose built-in APIs to save time for simple cases.

We have different mechanisms for reducing end-to-end latency around RAG and active learning, but I won't go into them in this post, as they target a different angle of how to improve CoPilot performance and reliability and would require another blog.

Engineers can decide to hide fields from the CoPilot explicitly.

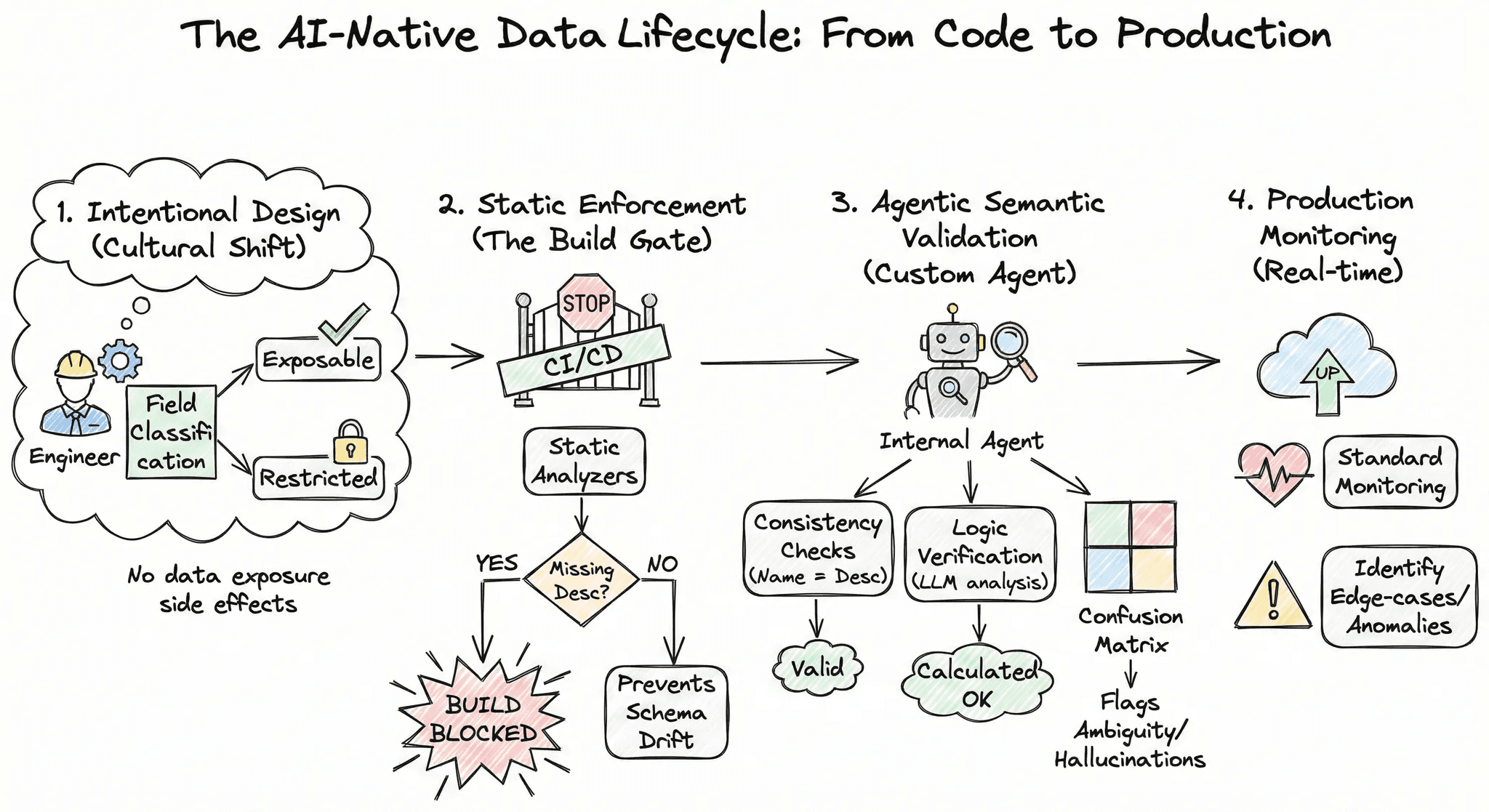

The AI-Native Data Lifecycle: From Code to Production

*Yes I used Gemini to make this ridiculous diagram, it seemed only fitting given the topic. And it gets the job done!

1. Intentional Design: The journey begins with a cultural shift in how our engineers view data. During the initial design phase, engineers must explicitly classify every new field as either exposable or restricted. This ensures that data exposure is never a side effect, but always a conscious decision.

2. Static Enforcement: We utilize static analyzers to enforce our documentation standards: if a field is marked for exposure but lacks a clear description, the build is blocked. This rigid enforcement prevents "schema drift," ensuring that no new data points are silently added or forgotten without a clear contract.

3. Agentic Semantic Validation: We have developed a custom internal agent specifically designed to validate our data integrity. Rather than relying on basic syntax checks, this agent performs deep semantic analysis:

Consistency Checks: Validates that field names align perfectly with their descriptions.

Logic Verification: Analyzes calculated fields to ensure the underlying logic matches what the name implies to an LLM.

Confusion Matrix: Proactively flags near-duplicate fields or ambiguous naming conventions that could cause "hallucinations" or mix-ups during inference.

4. Production Monitoring: Finally, we maintain standard production monitoring to identify and resolve any edge-case issues or anomalies in real time.

Many Databases, Many Truths

Okay, so far so good, right? I wish it were that easy.

As I continued building, I found that this gets harder as systems mature. Real products don't query a single database. You have an operational DB, an analytics store, a warehouse, a lakehouse, documentation, and now APIs via MCP. The same concept ends up in multiple places with slightly different names or shapes. The model has to guess whether account, tenant, and org are the same thing or three different ones. We check for that too: the same entity exposed under different names across different sources, creating ambiguity.

Principles for AI-Native Infrastructure

To sum it up, when building CoPilots that run Text2SQL tasks, we should follow principles that make the CoPilot more reliable (alongside the well-known database metrics we follow, such as performance). Just as we follow SOLID principles when writing code, below is a suggested modified SOLID (or SDDID) for AI-Native infrastructure:

Semantic Naming: Table and field names must be self-explanatory. If is_external refers to an email domain and not a user's status, it must be renamed or aliased for the AI.

Dialect Alignment: The schema should match the mental model of the user. If your customers ask about "Ownership," don't hide that relationship behind technical jargon like responsible_for. Your database dialect must speak the same language as your business.

Documentation: Every exposable field must have a description attribute. This metadata shouldn't live in a separate Wiki; it should be part of the database contract.

Intentional Exposure: Not all data is for AI. Use "AI-Exposability" flags to hide internal flags, version counters, and migration leftovers that confuse the model and waste tokens.

Drift Detection: Implement automated "Semantic Tests" in your CI/CD. If a new field is added without a description or violates naming conventions, the build fails. AI-readiness is a first-class citizen.