n8n Credential Sharing: Ownership vs Control

Jan 15, 2026

|

Amir Hamenahem

Explicit Sharing, Implicit Availability, and Administrative Impersonation

Automation platforms rely on credentials to execute actions under a user’s identity. In n8n, credentials are created by individual users and are commonly perceived as personal, especially when they live in a user’s personal project and aren’t explicitly shared.

In a multi-user n8n instance, though, “who created the credential” and “who can use the credential” are not always the same thing. Credential availability is governed by several mechanisms. Some are explicit and intentional. Others are implicit and easier to miss. The difference matters because it directly impacts identity use, accountability, and auditability.

The observations described here are based on direct experimentation in the n8n Cloud environment.

Credential sharing models in n8n

n8n provides multiple ways in which credentials can be used by users other than their creator. These mechanisms differ in consent, visibility, and scope.

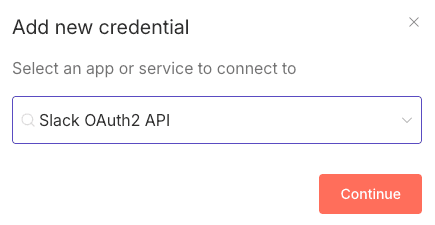

Explicit credential sharing

A credential owner can explicitly share credentials:

With specific users

With specific projects

Once shared, other users can execute workflows using those credentials.

This model is straightforward: the owner makes an intentional sharing decision, and other users gain access within the boundaries of what was shared.

Implicit credential availability

In addition to explicit sharing, credentials may be usable by others through implicit relationships.

Implicit case 1: Project-wide credential usage

If user A (member or admin) creates credentials in a project, other members of that project can execute workflows using those credentials, acting on behalf of user A.

This applies even if the credentials were not explicitly shared with each individual member.

In this case, credential usage remains scoped to the project, but the key detail is that “created in the project” can function like “available to the project,” even when individual user-to-user sharing never happened.

Implicit case 2: Instance admin usage across personal projects

A user can create credentials in their personal project and avoid sharing them with any other user or project.

Despite this, an instance admin can:

Create a workflow in the admin’s personal project

Select the user’s personal, unshared credentials

Execute workflows using those credentials

This does not require:

Credential sharing

Shared project membership

Notification to the credential owner

Additional consent

In other words, credentials created in personal projects are still usable at the instance level by administrators. Practically, “personal” describes where the credential is stored, not who ultimately controls its use.

OAuth example: Slack credential reuse

OAuth-based integrations make this behavior especially observable because consent is usually visible to the user.

Here’s the sequence:

A user authorizes n8n to access Slack via OAuth

Tokens are issued under the user’s identity

Credentials are stored in the user’s personal project

The user executes workflows using those credentials

An instance admin creates a workflow in the admin’s personal project

The admin selects the user’s Slack credentials

No OAuth re-consent occurs

The user is not notified

The workflow executes

Actions occur under the user’s identity

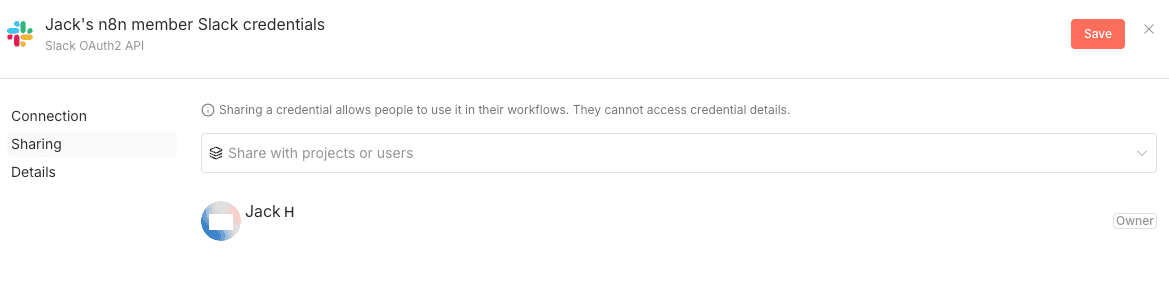

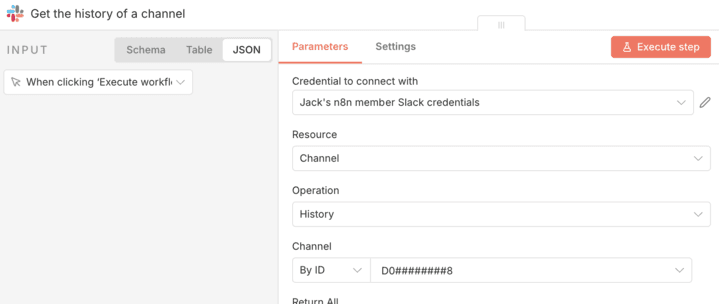

Jack, a member of the organization, creates Slack credentials scoped to his personal project.

Jack does not share his credentials with anyone:

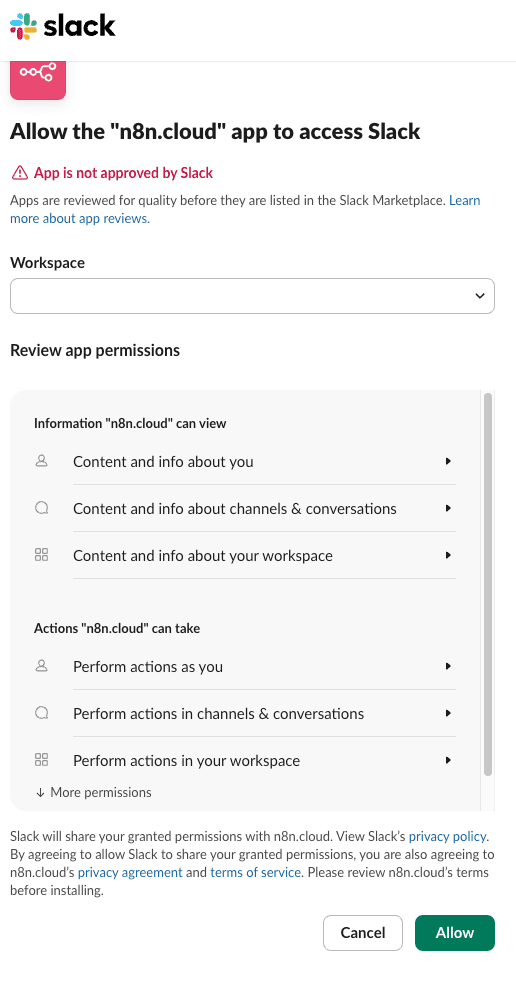

Jack approves the scopes:

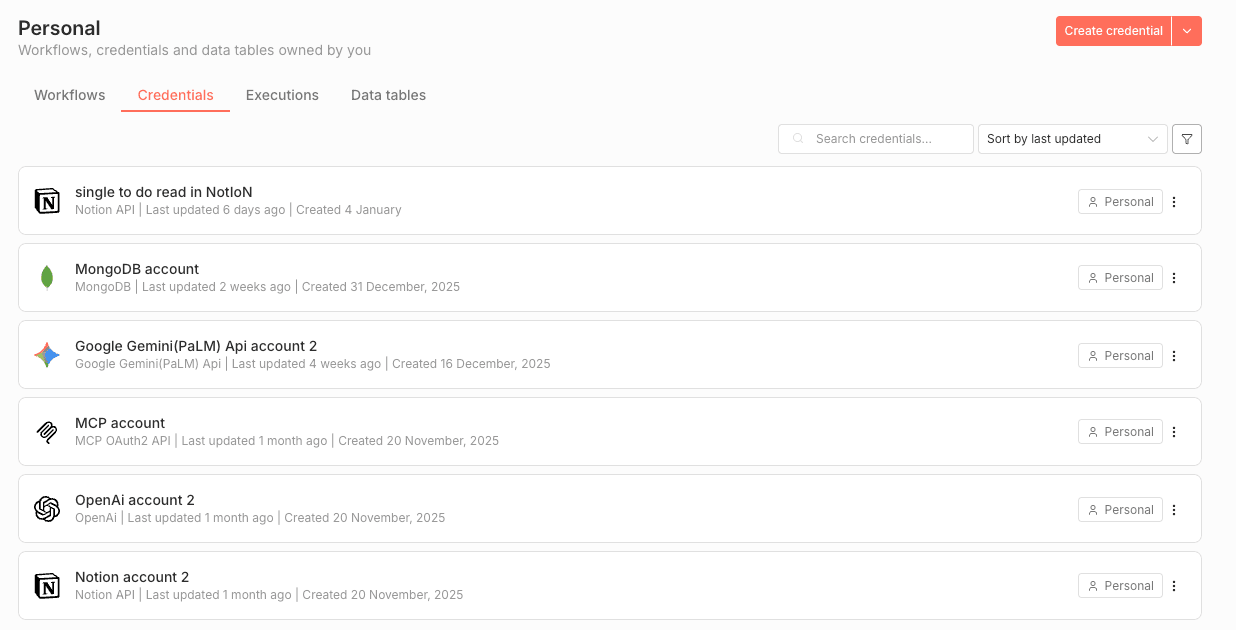

Later on, the instance admin’s own credential set is visible and does not include credentials for Slack.

When the admin creates a new workflow in the admin’s personal project and adds a Slack node, the list of available credentials includes credentials created by other users. Among them are credentials created by Jack, a member of the organization, which were created in Jack’s personal project and not explicitly shared.

The admin can select Jack’s credentials and execute the workflow.

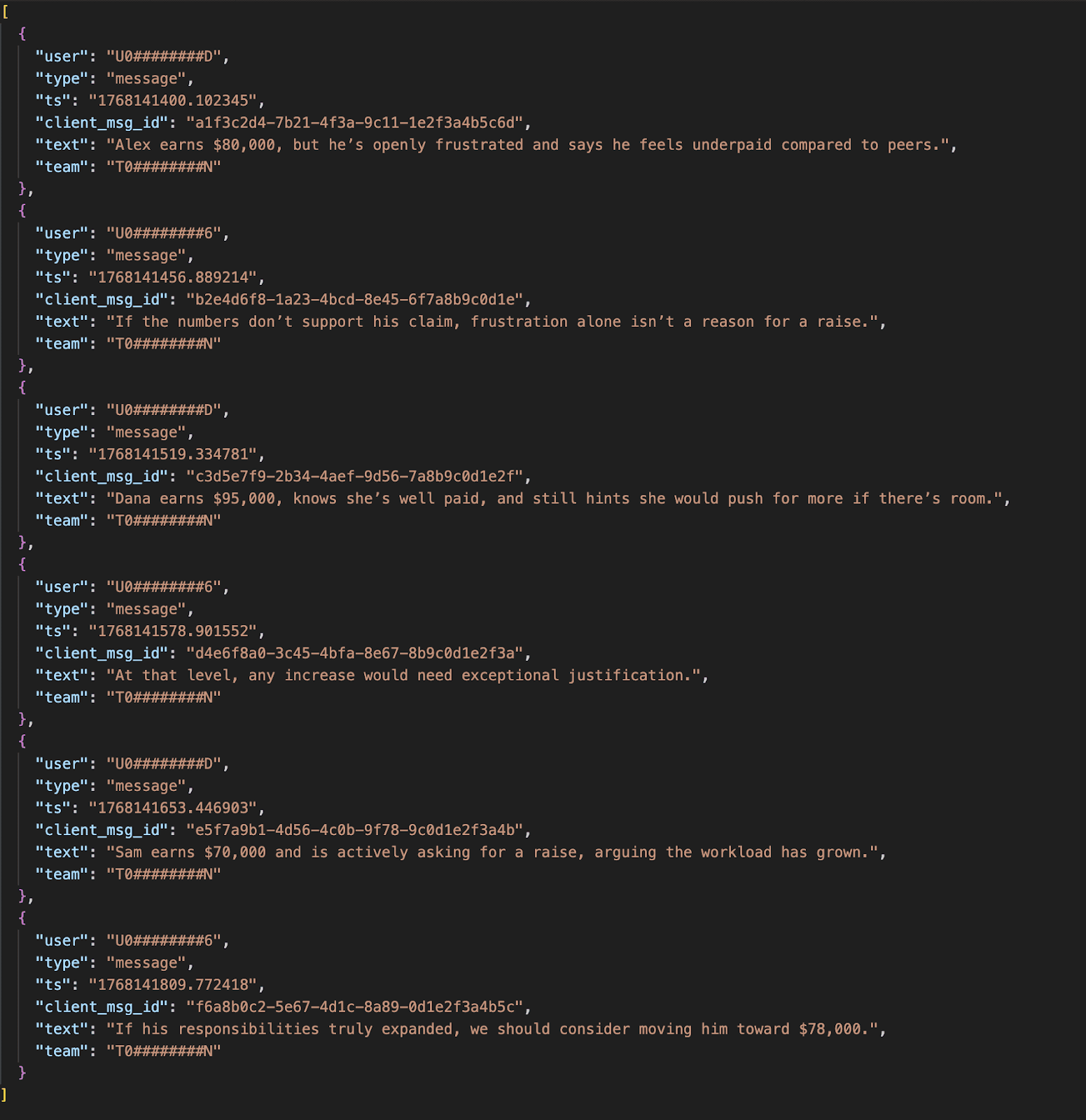

When the workflow is run by the admin, using Jack’s credentials, the resulting data corresponds to Jack’s Slack context. In an experiment we conducted, this allowed the admin to access sensitive information from Jack’s Slack channels, including messages containing salary-related information.

From Slack’s perspective, there is no distinction between actions initiated by the user and actions initiated by an admin using the user’s credentials.

What we validated in practice

In our test, an instance administrator was able to create a separate workflow and run it using another user’s Slack OAuth credentials that were stored in that user’s personal project and not explicitly shared. The workflow executed successfully without re-consent and without alerting the credential owner.

This is the core point: an admin can operationally “become” the user inside downstream systems, because downstream systems only see “valid token for user X,” not “who clicked run in n8n.”

n8n documentation and credential control

n8n states in its public GitHub repository:

“Instance owners and instance admins can view and share all credentials on an instance.”

That statement accurately describes administrative visibility and sharing capabilities.

What it does not explicitly state is that instance admins can execute workflows using credentials created by other users, including credentials stored in personal projects and not shared.

“View and share” and “run as the user” are materially different operations. The former suggests administrative oversight. The latter enables administrative impersonation in downstream systems.

Implications

This model introduces several effects that are easy to underestimate:

Actions are attributed to the credential owner. Downstream logs reflect the user whose token is used.

Credential owners cannot distinguish their actions from those performed by admins using their credentials.

OAuth consent granted by a user applies beyond that user’s control. The token’s effective authority can be exercised by others.

Credential boundaries align with instance authority rather than user intent. “I didn’t share it” is not the same as “nobody else can use it.”

These effects result from the credential availability model, not from a vulnerability or misconfiguration.

Trust model

n8n’s design assumes that instance administrators are trusted to operate using any credentials present in the instance.

In some environments, that assumption is acceptable. In others, especially those with shared administration, separation of duties, strict audit requirements, or regulated workflows, it may not match organizational expectations.

If your internal model is “admins manage the platform but cannot act as end users,” n8n’s behavior conflicts with that model.

Why this matters for agentic governance

Automation tools are increasingly used as execution layers: they connect systems, move data, and take actions with delegated authority. Whether you call them “automations,” “workflows,” or “agents,” the governance question is the same:

Who can cause actions to occur under a given identity, and can you prove who did what?

In this model, credential ownership (who created the credential) can diverge from credential control (who can actually use it). That gap is where audit and accountability get blurry.

Takeaway

In n8n, credentials can be made available through:

Explicit sharing by the credential owner

Implicit availability within a project

Implicit availability to instance administrators across personal projects

While n8n documents that admins can view and share credentials, it does not explicitly document that admins can execute workflows using unshared personal credentials and act under another user’s identity.

Organizations operating n8n should treat credential storage and OAuth authorization as instance-level trust decisions, and communicate that clearly to users.

This paper describes behavior, not intent. It clarifies where credential control actually resides.

Agentic governance with Linx

Most IAM teams already have a set of routines that work: access reviews, ownership assignment, least privilege, and remediation. Linx incorporates agentic identities into the same platform you use to secure and govern human and non-human identities across SaaS, cloud, and on-prem applications. That keeps visibility and governance consistent, even as identity types expand.

Read more about it here: Agentic identity discovery and governance with Linx